Debasish Mishra

Debasish Mishra

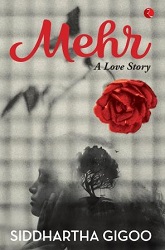

Mehr – A Love Story | Fiction | Siddhartha Gigoo |

Rupa Publications, 2018 | ISBN: 978-93-5304-365-0 | Pp 205 |  295

295

Love over politics and patriotism

Armed with an uncanny plot and peppered with poetic language, Mehr (2018) by Siddhartha Gigoo is more than a love story. It moves beyond the theme of love and explores the subtle facets of religion, patriotism and, more importantly, the working of the human mind. The novel is set in Kashmir, Karachi, and what is called, “a secret place”, along with passing references to London and Delhi.

At the outset, the novel promises to showcase the love between Mehr, a Shia woman from Pakistan, and Firdaus, a youngster from Kashmir, and the follow-up undertaken by Major K, a tenacious officer of Indian intelligence. The latter engages a Kashmiri youth, who assumes the role of the narrator for the most part, to track the conversations of the two lovers. The sudden appearance of Dr. A sheds light on the mental condition of Major Sridhar Kaul, which ensues a lot of confusion, albeit the author tries his best to ensure that the story is transmitted properly.

There are apparently two narrators: one, the unreliable narrator, initially deemed to be the “recruit”, at the helm of affairs for most part of the plot; and the other, the omniscient narrator who briefly follows after the moment of anagnorisis in the novel. Akin to the author's prize-winning story “The Umbrella Man”, Mehr also delves into the realm of the surreal, which may be regarded as a liminal space between dream and reality. The story unspools gradually, with shocks, surprises and suspense, and the reader, on his part, passes through a multilayered terrain.

Although the title seems to suggest that the novel would largely focus on the eponymous lady, it is not exactly the case. The unreliable narrator, most would agree, emerges as a significant character, arousing more empathy and feeling than Mehr or Firdaus. The narrator himself admits, “After all I am a part of the story, an integral part!” (51). His identity-crisis forms the crux of the story. Due to his dissociative identity disorder, he reflects two persons rolled into one. His awe for Major K can be interpreted as narcissism, or more aptly, as his rootedness in the past where he was a “hero” in the Indian army. Major K apparently tells the narrator, “I'm the best operative in the entire country” (141), thereby showing his own admiration for himself. This claim is testified later by Dr. A. Moreover, the narrator outlives the other characters in the work. The presence of Mehr and Firdaus, on the contrary, is confined mainly to their email correspondences, sprawled across the novel. With regard to the channel of communication, Hina, most often, writes letters to her brother Firdaus as well. In this context, Mehr has certain aspects of an epistolary novel.

The beginning of the novel with “her last words”— “If my end is horrible then begin my story at the end”— is reminiscent of T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding”:

“What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from.”

It not only marks a radical departure from the traditional structure of a novel but also hints at the lack of coherence in what is to follow. The engagement of an unreliable narrator, who aspires to “enter into the skin of these two people [Mehr and Firdaus]” and “become their voice”, helps the cause (51). In an interview to Hindustan Times, the author claims to be a “slave to his characters”, who are unique and autonomous with independent voices, representing Bakthinian polyphony. Manisha Gangahar, writing for Scroll.in, aptly observes, the characters here are “Rhizomatic selves, fluid and entailing a multiplicity of desires and sociological forces”.

The conflict between the Shias and Sunnis in Pakistan is brought out clearly in the early pages. The barbaric killing of the Shias in Karachi, which the author regards as “sheer madness” (40), is portrayed with photographic clarity, along with other superstitions and traditions. The author attempts to link the narrative with history, as in the case of Mehr, who is born on 16 December, 1971, the day when Pakistan surrendered to India and Bangladesh was born out of East Pakistan. This connection, in all likelihood, is the author's way of infusing life in his characters and making them more real.

The author prefers unmistakable objectivity at times, when he displays the data in a direct and pristine form, as in the patient admission form of Mehr and the medical report of Major Sridhar Kaul presented by Dr. A. Their confinement in the respective report cards shows the futility of their struggles. In both the cases, the family history of the individuals is categorised as “Unknown” (33, 183), thereby hinting at the emptiness of their lives. They are anonymous figures, across the border, reflecting the ordeal of a generation.

At times, the unreliable narrator converses with the readers, as in the chapter “The Convert”. He informs the readers, “I am going to tell you about an incident that I had never thought would happen Don't ask me how I know about it “ (153, Emphasis my own). This indicates how the author tinkers with the narrative with the use of metafiction.

The author has done well to avoid unnecessary jingoism. He prefers love over politics and patriotism. This is evidenced in Major Kaul's distraction from his duties and in Mehr's dismissive attitude towards the two countries and borders in between when she says, “Damn the two countries... I live for Pakistan. But I shall die for India” (26). The author, in an interview to News Nation, opines, “Love is an annoyingly difficult emotion to experience and understand”. This is reflected in the novel as well in the several troubled relationships. When the novel is subtitled as 'A Love Story’, it does not merely speak for Mehr and Firdaus, but discusses at length several other subplots, which include Mehr’s love for the little girl Zainab, the bonding shared between Firdaus’ sister Hina and Zafraan and their collective passion for music, the triangle between the endeared cat Ms. Mishima, Major K and the narrator, and Major K’s affinity towards Mehr. Mehr writes in one of her letters to Firdaus, “Lovers might swear by our name and separation”. This elevates the love of the pair, making them comparable to Romeo and Juliet, besides alluding to John Donne’s “Canonisation”, where the poet had endorsed their “pattern of love” for the future generations.

The identity of the narrator crumbles at once when it is clarified that he himself is a renegade, Major Sridhar Kaul, presumably Major K. This point of anagnorisis, apart from showing the author's knack of unpacking the suspense, questions the veracity of everything that the narrator had shared till that very moment, his credentials of hacking the conversations pertaining to the cross-border love story and his ability to fit into the shoes of the lovers. It forms the climax of the story, which shifts the focus from Mehr and Firdaus to Major Kaul and his surreal world.

However, there are certain aspects in the novel which undermine it. For instance, in the email correspondences, the beauty of Mehr is elaborately described time and again. Similarly, Mehr’s desire to meet Firdaus, although necessary to mirror the intensity, is repeated throughout the letters to little effect. Such excesses do not serve the purpose and appear drab and inconsequential. Furthermore, the language, at times, becomes superfluous and poetic, thereby distancing the plot from reality. The narrative structure, though not loose, is not tightly knit either, thus, giving room to ambiguity, incoherence and consequent difficulty.

Barring these minor glitches, the novel leaves no stone unturned. The end of the novel is cataclysmic with the sudden appearance of smokes and stealth jets in an isolated place in the vicinity of the border. Major Kaul, who had been a “hero”, is now “a renegade without a country, stripped off his title and decorations”, during the crisis (205). Yet he comes out of his tent to give a “resounding war cry” before returning to the trench (205). Ms Mishima, the cat, “his loving companion”, follows him, thereby showing her unflinching love for her master, at a time when everyone and everything had deserted him (205). If the beginning was an allusion to Elliot, so is the end. As Eliot celebrates the feline charm in Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats (1939) and other notable poems such as “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”, Siddhartha Gigoo considers Ms. Mishima as Major Kaul’s friend in need. The novel has many layers, similar to what Harold Pinter regarded as a “forest of possibilities”, and the reader forms his own inferences. The narrator has an invaluable piece of advice in the middle of the novel, when he suggests, “At the end, you decide what is truth and what is falsehood” (50). The ball, thus, rests in the court of the reader.

Issue 85 (May-Jun 2019)

- Atreya Sarma U: ‘Thrills & Chills’

- Basudhara Roy: ‘Making of the Indian Muse – Context and Perspectives in Indian Poetry in English’

- Debasish Mishra: ‘Mehr – A Love Story’

- Jindagi Kumari: ‘the Origins of Dislike’

- Lakshmi Kannan: ‘A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There’

- Priyadarshi Patnaik: ‘Monsoon Feelings – A History of Emotions in the Rain’

- Robert Maddox-Harle: ‘Intersections – Visual, Verbal’

- Semeen Ali: ‘Gulzar’s Aandhi’